COVID-19 has ushered in a new wave of industry automation.

How can we make this work best in the service of humanity?

By: Carlos Lemos

The COVID-19 pandemic has ushered in a new wave of automation; in the medical space alone, it has reinforced patient’s’ access to telemedicine via remote consultations, the use of health-monitoring apps; as well as wider societal changes from a shift to remote working to online shopping, with e-grocers using robot-enabled warehouses. How can we ensure that this new wave of robots, automation, and remote working work in the service of humanity, avoiding depersonalisation, or the degradation of our environment?

Automation consists of the employment of machines and technology in several human activities. The invention of the steam engine during the Industrial Revolution (1760-1840) has revolutionized the industry sector, along with the development of new systems of production, exchange and distribution. Since then, automation has changed not just the industry sector, but also how people see themselves, relate to one another and interact with the natural world. The most cited advantage of automation is the increase in productivity, with reduced labor costs, allowing to perform tasks that previously needed many more people to accomplish. This represents an opportunity to relieve humans from hard, physical and repetitive work, therefore avoiding occupational injuries.

The installation of a new equipment usually requires a high initial capital expenditure, since its advantages may not materialize instantly, demanding an incremental approach. Productivity will eventually surge over time, with the rise in profits allowing firm expansion. The declining cost of automated production may eventually place at risk those workers in low skill jobs engaged in routine tasks. It is estimated that, by 2030, between 3 and 14 percent of the global workforce will be forced to switch job categories due to automation eliminating jobs in an entire sector.

On the other hand, the number of jobs lost to automation is often offset by jobs gained from technological advances, contributing to a higher demand for highly skilled labor. Although humans tend to be less involved in the automation process, their contribution still displays a critical role, since if the system has an error, it will multiply until fixed or shut down. Given that, human supervision becomes crucial when implementing an automated process, since uncontrolled production, without human intervention, can result in a chain of unchecked spread of defects. A recent Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report concluded that countries with higher rates of automation since 2012, saw stronger employment growth, consistent with the idea that technology adoption leads to higher productivity. A study on Japanese industry has found that following the acquisition of one robot unit per 1,000 workers, company’s employment rose by 2.2%.

Automation also presents a significant opportunity to improve both efficiency and quality of healthcare. Nowadays, clinical laboratories are already equipped with fully automated analytical systems, allowing high-throughput screening. Here, technology has an utmost relevance in increasing diagnosis accuracy, translating into better patient outcomes, while reducing low-value procedures, such as duplicate exams or unnecessary treatments. However, automation of key aspects of care to deliver greater efficiency might do so at the expense of meaningful human interaction. At this level, automation also has the potential of relieving more time for healthcare providers to focus on human-to-human relation, allowing, for instance, to strengthen patient-doctor relationship.

Human supervision becomes crucial when implementing an automated process, since uncontrolled production, without human intervention, can result in a chain of unchecked spread of defects.

The COVID-19 pandemic has reinforced patients’ access to telemedicine via remote doctors and the use of health-monitoring mobile-phone apps. Actually, we are witnessing a shift from hospital-based to home-based care, with patient empowerment, through self-care, remote monitoring, alerting systems and virtual assistants. At the same time, COVID-19 also triggered several social changes, reinforcing the trend towards automation. Lockdowns have demanded home working, giving rise to a boom in e-commerce, with significant modifications in the supply chain, with an increase in warehousing all around the world. Following this trend, machines have become indispensable in picking and packing an exponentially rising number of items. In the coming years, machines will increasingly work in supermarkets, clinics, social care and much more.

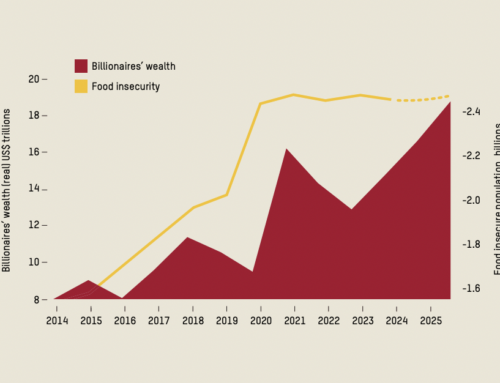

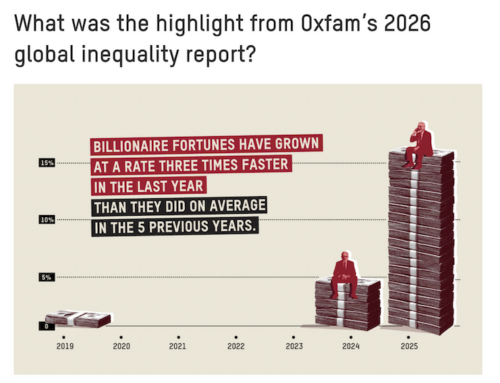

Although automation has the potential to expand human capability, there are several pitfalls that must be taken into account, such as de-humanisation of work, unemployment of low skill workers engaged in routine tasks, or the environmental impact of some automated processes, for instance, those that use hazardous industrial chemicals, generating waste and producing air and water pollution. Technological innovation can help to redress inequalities, but conversely also has the potential to exacerbate them. Consideration must be given to how they affect equality and equity, including the risk that vulnerable groups might be excluded or exploited.

We should keep in mind that automation is a means to an end, not an end in itself, since “The goal should not be that technological progress increasingly replaces human work, for this would be detrimental to humanity. Work is a necessity, part of the meaning of life on this earth, a path to growth, human development and personal fulfillment”. When redesigning or implementing automation, we should focus on what actually matters to people. Machines shall work alongside human beings, not replace them.

If wisely and effectively addressed, automation can yield substantial opportunities to provide social and growth, in a way that humans can enjoy a higher standard of living and a better way of life. Technology shouldn’t overshadow human relations, but deepen the reflection on human nature and its unreplaceable features. Actually, the “incredible breakthroughs in autonomous and thinking machines, which have already in part become components of our daily lives, lead us to reflect on what is specifically human and what makes us different from machines”.

References

SCARPETTA S, PEARSON M, What happened to jobs at high risk of automation? OECD, 2021. URL https://www.oecd.org/future-of-work/reports-and-data/what-happened-to-jobs-at-high-risk-of-automation-2021.pdf

Adachi D, Kawaguchi D, Saito Y, Robots and Employment: Evidence from Japan, 1978-2017. Discussion Paper 20-E-051, RIETI, 2020.

The future of work after COVID-19. McKinsey Global Institute, Feb 18th 2021.

CARLOS LEMOS

Lisbon, Portugal.

Medical Doctor – Clinical Pathology Department, Centro Hospitalar Universitário Lisboa Norte (CHULN) E.P.E.

Professor of Laboratory Medicine – Faculty of Medicine, University of Lisbon.