The EoF Academy Researchers: Comments on the 2024 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences

Tracey Freiberg, PhD

Assistant Professor of Economics, St. John’s University, New York, USA

The Nobel committee awarded Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson (or “AJR”) [1] the 2024 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences for, “studies of how institutions are formed and affect prosperity.” [2] Specifically, the committee stated the importance of societal institutions and their role in influencing the prosperity of countries, and how AJR’s research influences the way in which we can shrink the income gap across the globe. For example, the laureates note that institutions established during colonization, and how inclusive (i.e. democracy, access to education for all citizens) or exploitative (i.e. slavery, insecure property rights) such institutions were with the local populations, influences how the country thrives (or doesn’t) today. [3] In a widely cited 2001 paper, AJR compare institutions implemented by European colonies, where “extractive states,” denoted by minimal protection of private property rights and the absence of checks on government expropriation, aim to transfer resources from the colony to the colonizer (i.e. the Belgian colony of Congo). [4] On the other hand, when settlers in a new colony tried to replicate their homeland, the colonial state had a higher likelihood of persisting after independence (i.e. New Zealand, Australia).

Such thinking is a notable departure from many mainstream economic tools. While older questions in economics needed to adhere to “laws”, modern applications of economics like we see in this year’s prize can help us answer more open-ended questions, leveraging both positive and normative analysis. Although the bulk of AJR’s work (for the Nobel) is focused on country-level analyses, many of the results can be applied to other stratifications of the economy to better understand and assist our young people, elders, citizens, friends, and neighbors.

In the Economy of Francesco, we hope to help foster a change in how economics is studied and taught. We favor a community-centered analysis versus one that focuses on individuals and firms, as evidenced by the glossary we developed in hopes of repairing the language of economics (now available in three languages, #shamelessplug). [5]

We recognize modern-day exploitative institutions and advocate for a better economy. We also value the global connections of Economy of Francesco members, and the perspective each person brings from their respective communities across the world. As we look to scholars such as Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson for ideas on how to combat poverty, per the Franciscan doctrine, we can leverage the new tools they have created to ignite our own economic contributions for a more equitable, sustainable, and fruitful future.

A note for scholars: since Dr. Acemoglu visited us in October 2023, involvement with the Economy of Francesco may be a good step toward your own Nobel Prize! [6]

—

[2] https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/2024/press-release

[4] https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/aer.91.5.1369

[5] https://www.uceditora.ucp.pt/en/traducoes/3317-the-economy-of-francesco.html

[6] Thank you to Paolo Santori for the idea: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0gdPd4ixfME

Complex Answers to Simple Questions

Serena Ionta, PhD

Post-Doc Researcher. Bocconi University, Milan, Italy.

“What are the fundamental causes of the large differences in income per capita across countries?” This question serves as the opening line of the 2001 AER paper The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation, authored by the 2024 Nobel Prize laureates Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson. A question that is so simple, concise, and direct can also be frightening due to the complexity of its answer. Indeed, many inquiries that appear straightforward—often posed by undergraduate students, for instance—can be surprisingly challenging, sometimes even impossible, to answer. In essence, it is a simple question that conceals a difficult answer. Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson successfully addressed this question, and for this achievement, along with many others throughout their distinguished academic careers, they were awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics.

The authors demonstrate that the differences in global wealth among countries can be attributed to the institutions that have existed over time and are, therefore, inherited today. As the Royal Swedish Academy stated, “They provided an explanation of why some countries are rich and others poor.”

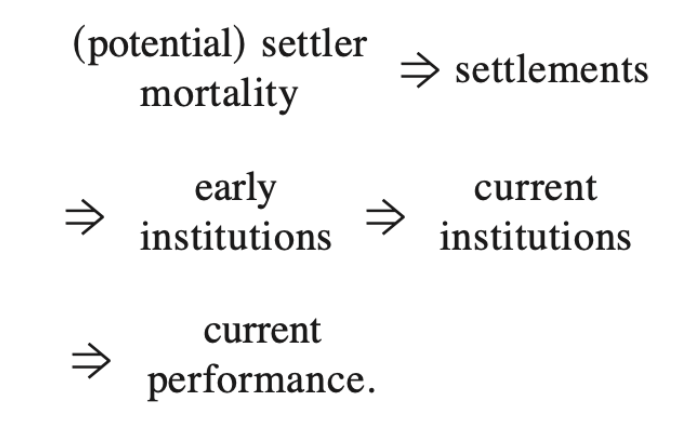

Through an empirical methodology, they specifically show that inclusive economic and political institutions were essential for achieving long-term prosperity. They do this by studying the different European colonization policies, which led to the establishment of distinct institutions in each country. Proving this is challenging, because a correlation between institutions and prosperity doesn’t automatically imply causation; applied economists and statisticians are well-versed in the distinction between correlation and causation, pointing to the challenges in isolating the effects of reverse causality. In this context, for instance, low economic growth and prosperity might impede the development of institutions, meaning that prosperity influences a society’s institutions, rather than vice-versa. The authors solved this problem, using the anticipated mortality rates of the first European settlers in the colonies as a proxy for the contemporary institutional frameworks in these countries, thereby demonstrating the causal relationship between these institutions and economic performance.

Their theoretical interpretation has provided valuable insights:

For example, (1) colonial institutions varied significantly based on indigenous population density during European colonization. In densely populated areas, colonizers established extractive institutions that favored a local elite and limited political rights. In contrast, sparsely populated regions saw more European settlers create inclusive systems, encouraging investment and political rights, which shaped the long-term development of these colonies. Additionally, (2) they introduce the concept of “Reversal of Fortune” which refers to the paradoxical shift in prosperity observed in colonized regions, where areas that were once wealthy, like parts of Mexico, became poorer over time, while previously impoverished regions, such as those in North America, grew richer. They attribute this phenomenon to the types of institutions established by European colonizers: extractive institutions in densely populated areas hindered long-term prosperity, whereas inclusive institutions in sparsely populated regions promoted economic growth. The laureates have shown that another factor contributing to institutional differences was (3) the severity of diseases that spread through settler communities; regions with higher mortality rates were often the ones that experienced greater exploitation. Ultimately, (4) they also sought to explain why certain democratic processes were easier to implement in some countries compared to others, mentioning fears of revolution, a lack of mutual trust, and commitment problems as key factors.

In summary, the award to Acemoglu and his colleagues reminds us of the crucial importance of sustainability and the inclusiveness of institutions today—or, more precisely, the rules that govern societies made up of people living and interacting with each other. This connects to a recent interview conducted by the EOF community with Nobel laureate Acemoglu, in which he emphasizes the importance of technological progress and how it should be utilized and, above all, ‘distributed’ worldwide to ensure that no one is excluded and that everyone can exercise their rights.

This theme is central to economics and particularly resonates with the Economy of Francesco, especially when we understand institutions to include the political and economic participation of broad segments of the population, including the poorest and most marginalized.

As a community, we have consistently emphasized the importance of civil society as a fundamental institutional component driving not only economic development but also the social, anthropological, and cultural progress of society. Our efforts have always been aimed at promoting the integral development of the human person, which transcends mere economic prosperity while remaining deeply connected to it. We should not fall into the trap of distinguishing between “good colonialism” and “bad colonialism”, but instead focus on understanding the real forces that can combat global inequality today—beginning with institutions and drawing from the seminal and crucial research of Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson.

The notion that democracy lasts only when elites have no incentive to overthrow it is far from an adequate starting point. What we need is to advance ideas that encourage the global community to think, collaborate, and build a shared, sustainable, inclusive, and fraternal path, where we all belong to the same home and care for it together. In addition, as an international and multicultural community, it is crucial to recognize that development has many facets, effective institutions must be tailored to specific contexts rather than mere imitations of Western models. Truly inclusive and sustainable institutions should be grounded in local realities, drawing lessons from the diverse conditions required for a whole/integral development.

So, what lessons can we draw from this?

The idea that seemingly simple questions can hide more complex answers than they appear, potentially leading to significant innovations in literature and even shifts in scientific paradigms. Moreover, this Nobel Prize serves as a reminder to us scientists that we always start with simple questions—the same ones raised by undergraduate students and even those who are not directly engaged in this scientific field.

The final lesson is for us young researchers: there is much excitement and a great deal of work to be done, but most importantly, there is much to discover.

—

References

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2001). The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation. American Economic Review, 91(5), 1369-1401.

The Prize in Economic Sciences 2024. (2024). Popular Science Background. Retrieved from: https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2024/10/popular-economicsciencesprize2024.pdf