At Rio’s G20 Social Summit,

the Promise of a New World Economy

The first social meeting of the G20, held in Rio de Janeiro, brought forward possibilities for reconfiguring the global economy to address pressing social and environmental challenges, though much progress remains to be made.

by Lucas Prata Feres*

Between November 14 and 16, I gathered in Rio de Janeiro alongside thousands of economists, social scientists, representatives of social organizations, activists from social movements, and political parties from around the world for the first G20 Social Summit. This initiative, launched under Brazil’s G20 presidency and led by President Lula, marked a new era of social participation in major global decision-making forums, filling the void left by the decline of the World Social Forum.

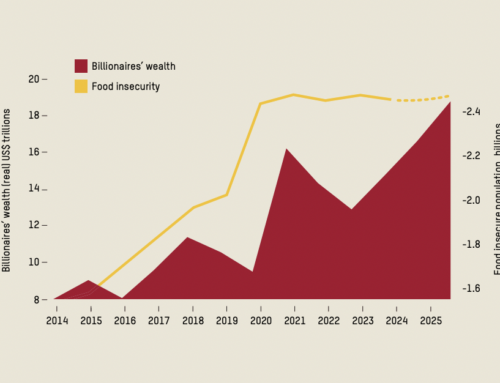

The final document of the summit, delivered to the G20 leaders, addressed the three priorities defined under Brazil’s presidency of the group: combating hunger, poverty, and inequality; sustainability, climate change, and a just transition; and the reform of global governance institutions. The G20 meeting in Rio de Janeiro also saw the launch of the Global Alliance Against Hunger and Poverty, joined by 82 countries and dozens of non-governmental organizations.

This mechanism for coordination and collaboration among nations aims to reach 500 million beneficiaries through income transfers by 2030. Currently, over 700 million people worldwide face hunger.

Fighting hunger and poverty is not just a moral imperative; it is also an economically sound measure. By overcoming poverty, individuals can contribute productively to their country’s development, boosting economic productivity and including marginalized populations in society and the consumer market. This approach effectively extends the boundaries of the economic system. In the 21st century, hunger is more than ever a political and monetary issue, stemming from a food production and distribution system that does not prioritize meeting the dietary needs of the population.

Shouldn’t we, the people, demand the design of a global system ensuring food security, with part of the economic structures of all countries coordinated internationally to organize the most efficient supply chains to guarantee healthy diets for everyone? What real obstacles exist to establishing a multilateral framework for this purpose? This is the essence of transforming economic systems: ensuring that at least part of economic activities and resources are directed toward meeting the needs of the population through international cooperation, which enables various national actions. As Pope Francis puts it, local politics alone cannot solve global problems.

The same spirit of international cooperation is crucial for addressing environmental issues. Humanity is living its final moments in which it still has the capacity to secure its long-term existence on the planet—there is no time to waste. The challenge is monumental: it involves a large-scale ecological transition, rethinking production processes, redefining energy sources, rebuilding urban infrastructure, mitigating the immediate effects of climate change, and reshaping economic growth toward low-impact activities.

This transition to a low-carbon economy must also be fair. Countries historically responsible for the highest emissions, having enabled their industrialization since the late 19th century, must contribute proportionately more to financing this transformation. This funding should also prioritize developing countries that have yet to complete their industrialization processes, allowing them to advance income and employment generation capabilities based on environmental sustainability.

In addition to financing, this transformation will require technology transfers and trade policies that benefit the development of poorer nations. Yet, we are far from achieving this. Even proportional contributions from wealthier nations are not assured, as they seek ways to impose greater burdens on developing countries. Achieving convergence toward less unequal levels of global development alongside climate transition requires historically responsible nations to act in solidarity and cooperation. This includes financing various national transitions in a planned and coordinated manner.

The G20 Social Summit’s final declaration also emphasizes the centrality of decent work in overcoming poverty and inequality, though it delves little into the subject. At this historical juncture, labor as a commodity has reached its peak, increasingly disconnected from the needs of workers. Guaranteeing decent work for all job seekers will require rethinking what labor is and how it is created, extending beyond national macroeconomic policies.

For instance, securing adequate food in every country could involve coordinating a network of agricultural production cooperatives tailored to local characteristics, with guaranteed purchases by a regional food stock regulation organization. Similarly, investments in clean energy production in various countries could come with requirements for employment conditions aligned with ILO standards for decent work.

The third priority of the final declaration concerns reforming global governance institutions to strengthen multilateralism and promote democratic regimes and social participation, particularly in the most influential decision-making forums of the United Nations system. This reform reflects the shifting power dynamics among nations, with emerging economic powers in the Global South gaining prominence.

Additionally, a global framework must not only ensure peaceful coexistence among nations but also foster significant advances in collaboration to address cross-border challenges like environmental crises and health threats. Peacekeeping is only the beginning of this necessary institutional evolution.

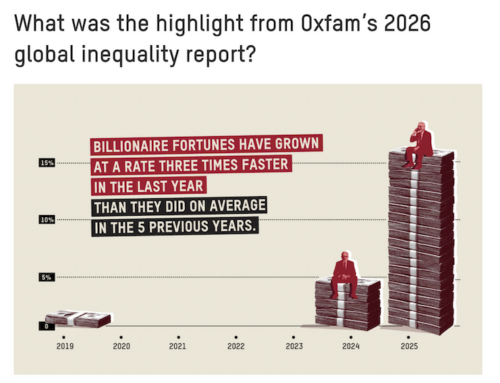

A notable absence in the declaration is financial regulation. Many contemporary international economic issues stem from the high mobility of global capital flows, destabilizing peripheral countries’ external accounts and making them reliant on liquidity cycles to finance development. Addressing this requires greater stability and control over global capital movements and national financial centralization institutions capable of driving productive restructuring projects tied to higher income levels.

The global financial regulatory framework outlined in the Vatican’s Oeconomicae et Pecuniariae Quaestiones, emphasizes the legitimacy of gains that do not compromise the holistic promotion of human dignity. It underscores the social role of credit and enterprise. A new financial regulation must tackle issues such as joint credit and investment management in banks, the lack of transparency surrounding financial products and risks, the shadow banking system, and offshore finance.

In today’s world, we must reimagine the economy as a subordinate sphere of social life, tasked with addressing society’s goals rather than defining them through presumed universal truths. Humanity faces the monumental challenge of establishing institutional frameworks to allocate global economic resources cooperatively and collaboratively to address pressing global issues. The G20 Social Summit provided valuable insights into how this process could unfold, and it is now up to us to deepen this international economic agenda for the 21st century.

*PhD Student at the Institute of Economics, UNICAMP, Brazil – Contact: [email protected]