Ethics of the job well done

(translated from L’etica del lavoro ben fatto: una lezione per Primo Levi e per noi. Il racconto del muratore Lorenzo, la salvezza dello scrittore e la dignità del saper fare. Luigino Bruni, Ilsole24ore)

“The Italian bricklayer who saved my life by secretly bringing me food for six months hated the Germans, their food, their language, their war; but when they put him up walls, he made them straight and solid, not out of obedience but out of professional dignity.” This episode recounted by Primo Levi in many of his works has become a paradigm of the ethics of work well done, of the wall pulled up straight for reasons much deeper than incentive.

That mason’s name was Lorenzo Perrone, he was from Piedmont, from Fossano. He was a decisive person during Primo Levi’s stay in Auschwitz from February 1944 to June 1945. Now, thanks to Carlo Greppi’s beautiful essay (Un uomo di poche parole. Storia di Lorenzo che salvò Primo – A man of few words: The story of Lorenzo who saved Primo, Laterza, 2023), we know much more about Lorenzo, and we know more about Primo Levi:

“I believe that it is to Lorenzo that I owe being alive today… for having reminded me, by his presence, by his so flat and easy way of being good, that there still existed a just world outside of our own ” (If This is a Man, quoted on p. 144).

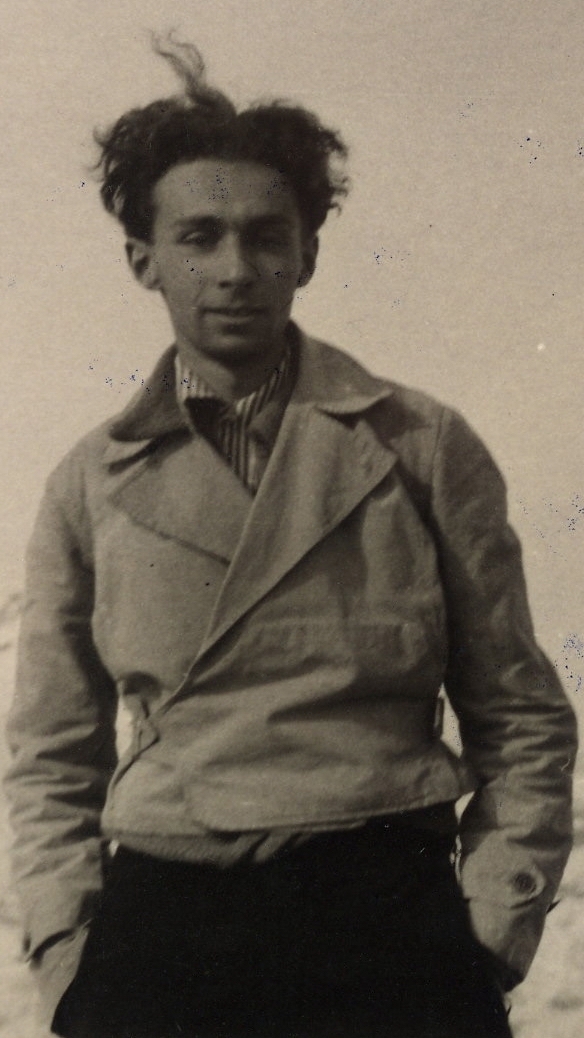

Lorenzo and Primo met at a construction site in Auschwitz (No. III, the Monowitz, the ‘Buna’), which was a kind of huge private labor camp. Lorenzo Perrone (the ‘Tacca’), from Fossano (the Burgué), emigrated to France during Fascism, and in 1942 ended up ‘seconded’ to a German firm (Farben), which worked in the Buna of Auschwitz-which Lorenzo called and spelled ‘Suiss.’ -under industrial agreements between Italy and Germany. He arrived to put up walls, and found himself rescuing Primo, and, as we find out at the end of the book, many other prisoners. So he was a civilian, a ‘volunteer,’ he was not Jewish, in theory a free man, as free as an Italian could be in Germany after September 8, 1943.

In February 1944 Primo arrived, No. 174517, he was 24 years old, Lorenzo almost 40. A chemistry graduate, Primo was destined to be a laborer in the Buna. One day in June, while trying to pass a casserole with mortar to Lorenzo on a scaffold, he made a wrong maneuver and the mortar ended up on the floor: “Oh yeah, you can tell, with people like this,” were Lorenzo’s first words in dialect, his only eight words that Primo reported in his books. Something wonderful was born between the two Piedmontese, that immense evil spawned a beautiful flower: “Look what you risk talking to me,” “I don’t give a damn,” Lorenzo replied (p. 105). “I did not study. To me a Jew is a Christian like any other” (p. 94). Two or three days after their first meeting, Lorenzo showed up at work with his aluminum alpine gavetta and handed it to Primo, “without saying a word at all” (p. 60).

A decisive element of this extraordinary story is revealed by Levi in two adjectives: ‘his so flat and easy way of being good.’ There are many ways of being good. The most common ones have to do with will. This voluntary goodness appeals to us, and it is fundamental to living. But there is also another goodness, Lorenzo’s ‘flat and easy’ goodness, where we do not feel we are the object of special ethical efforts, but are loved as if the other (almost) does not notice. It is a love similar to that of nature, of plants, of children, of some poor people. It is another love, very rare and beautiful.

An extraordinary friendship, among the most beautiful of those that have intersected with great literature, to be juxtaposed with that, imagined by Dumas, between Edmond Dantes and Abbot Faria in the Count of Monte Cristo (even in Auschwitz, not only in the Chateau d’If, inmates took the place of corpses to leave the camp).

An unlikely, asymmetrical friendship (Lorenzo called Primo ‘lei’ until the end), made up of very few words and infinite stupendous beauty, so important that it determined the names of Primo’s two children (Lisa Lorenza and Renzo): for a Jew, the choice of children’s names is always something extremely important. And Lorenzo senses this: “The greatest pleasure for me was that I put the name Lisa Lorenza on him so he will also bear my name but I hope, thanking the Lord, that he will not have to bear my sufferings that I have brought into my life” (p. 200). Lorenzo’s postcards, with his second-grade Italian, are among the most beautiful pages of the book, a song to the dignity of the poor and the defeated.

In the 1966 stage version of If This is a Man, Primo gives more words to Lorenzo: “Look, I have nothing to give you here. Maybe in Italy, later, if I get by.” “What speeches. I haven’t asked for anything. When something is to be done, it is done. Like walls” (p. 94). You love people the way you do walls, you save a ‘Christian’ because it has to be done, like walls that have to be done straight because it is done that way. Perhaps only that inhuman absurdity could give birth to this almost ultra-human beauty. Primo was always aware that something extraordinary had happened in that friendship: “Lorenzo was a man, his humanity was pure and uncontaminated, he was outside this world of denial. Thanks to Lorenzo it happened that I did not forget that I myself was a man” (If This is a Man, p. 144).

Work well done saved Lorenzo and, in him, saved Primo as well. But when in June 1945 after a five-month journey on foot he returned home from ‘Suiss’ Lorenzo stopped being a bricklayer.

Work no longer saved him. He began drinking, making a living selling old irons, sleeping around, always drunk. He fell ill with tuberculosis, and on April 30, 1952, Lorenzo died. Primo had tried to help him in every way, visited him every week when he was in the hospital. But Lorenzo did not want to live anymore, he had lost the will to live – ‘he had seen enough,’ p. 204 -, and he let himself die. He had saved Primo, but Lorenzo did not save himself.

Primo a few days after his return from Swiss had gone to visit him in Fossano, and as a gift he brought him a knitted sweater, made of goat’s wool, with a red border at the neck (p. 169), to give him back that woolen sweater that Lorenzo had given him during the dreadful winter of the lager.

Primo went to his funeral, pronounced a brief remembrance: he was wearing a white woolen sweater (p. 218).