Justice for Animals: Three questions to

Martha Nussbaum

by Paolo Santori, Assistant Professor of Philosophy (Tilburg University)

—

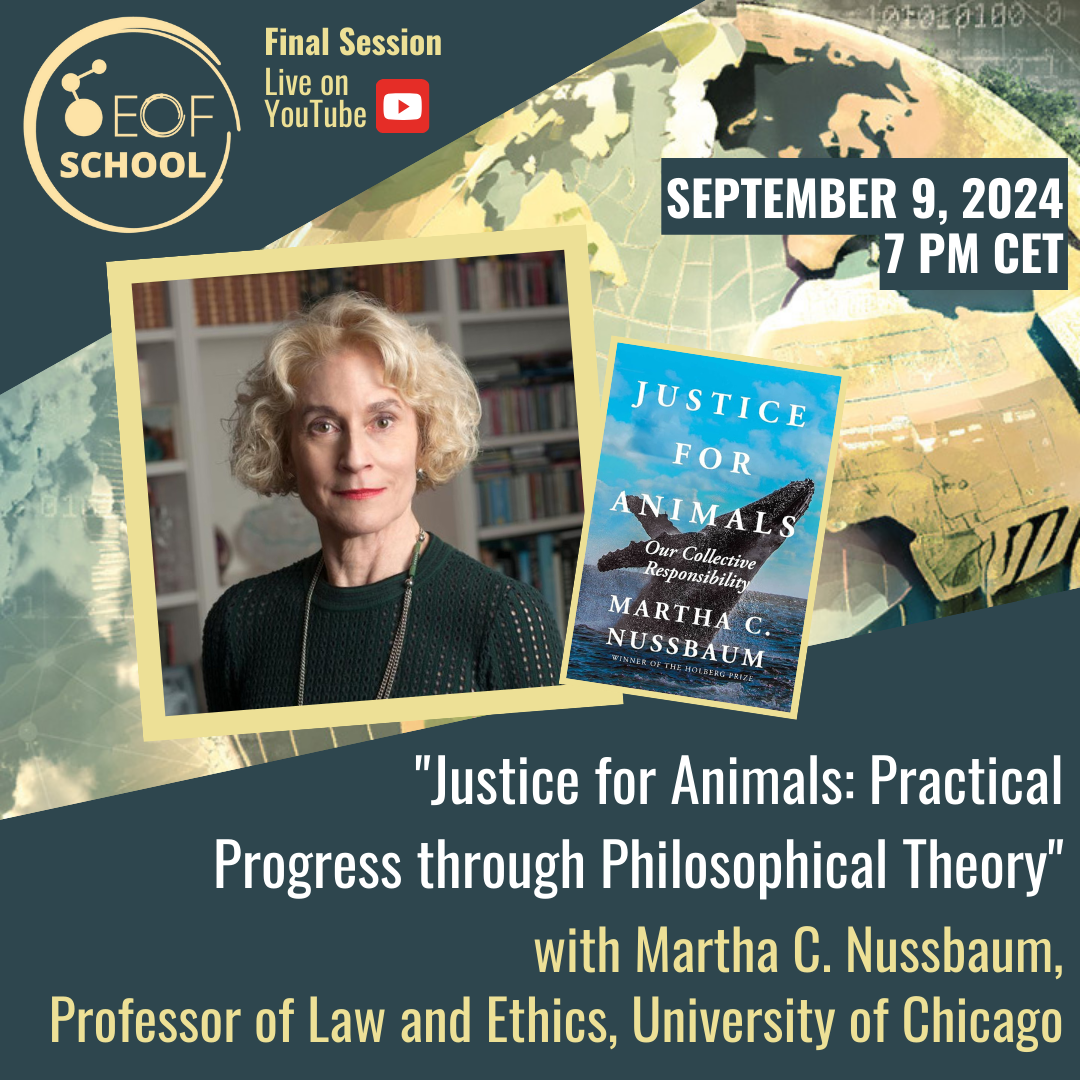

On Monday, September 9th, at 12:00 CT (7.00 pm CET), philosopher Martha Nussbaum will deliver a talk at the Economy of Francesco School, concluding the seminar series that featured distinguished guests, such as Sir Angus Deaton, Joanna Bryson, and Flavio Comim. Her lecture, titled “Justice for Animals: Practical Progress through Philosophical Theory,” was grounded in her latest book, Justice for Animals: Our Collective Responsibility, published in 2023 by Simon & Schuster. To introduce readers to the seminar’s theme (accessible for free on YouTube), Martha Nussbaum graciously agreed to answer some questions regarding her book.

PS: Professor Nussbaum, let me start by expressing my and the EoF community’s profound gratitude for your participation as a guest speaker in our EoF School.

MN: Paolo, I’m delighted by this invitation and very eager to make the acquaintance of your EoF community.

PS: I would like to begin with the title of your book, Justice for Animals. The first chapter introduces the concept that injustice affects animals not just through harm, but also through “wrongful thwarting” (p. 8) by human actions—impediments that block animals’ “significant striving” (p. 8). Additionally, you discuss three moral emotions, namely, “ethically attuned wonder,” “ethically directed compassion,”

and “forward-looking outrage” (p. 9), that can motivate people to care about the issue of animal justice. My first question pertains to the genesis of your book: Was there a particular instance of wrongful thwarting against animals that stirred your moral emotions and motivated you to embark on this project?

MN: First, please note that the full title of the book is Justice for Animals: Our Collective Responsibility. We are all responsible for rectifying the harms that, as a species, we have caused. No there is not just one example: examples are all around us: the cruelties of the factory farming industry, assaults on the habitats and life-activities of so many creatures. I begin the book with five examples of wrongful thwarting: a whale choked by plastic trash; a pig forced to live in a narrow metal box prior to being slaughtered; a bird choked by man-made air pollution; an elephant murdered for the ivory in its trunk; a dog abused by its “owner”. These are just samples, but they give a sense of the breadth and ubiquity of our bad actions. The project was inspired by my daughter’s work as a lawyer for animals. We co-authored several papers, and when she tragically died in 2019, having already embarked on this book project, I felt moved to carry it forward and to try to make it worthy of the quality of her compassion and dedication.

PS: The philosophical analysis in your book seeks to provide a foundation for political and legal actions. Central to your proposal is the Capabilities Approach (CA) that, in your view, should underpin a virtual constitution “to which nations, states, and regions may look in trying to improve (or newly frame) their animal protective laws” (p. 100). As worldwide scholars and the general public are familiar with your CA approach in the context of human flourishing, grounded in substantial freedoms and real opportunities to pursue what people value, one might wonder: Are there any differences or unique considerations when applying the CA to non-human animals?

MN: The similarity is that I define minimal justice in terms of a list of substantial opportunities for flourishing, as I did for humans. The difference is that for each type of animal there should be a different list, reflecting that species’s form of life, and of course with lots of latitude for individual variation within the species. The list is made in effect by the animals themselves as they go about their lives trying to flourish, but because we humans are in charge of the world we are the ones who must write down the lists and make laws promoting animal capabilities. The people who can be trusted to make these lists are people who have lived with and studied a given type of animal, with love and sensitivity.

PS: EoF is a community of young economists, entrepreneurs, and change-makers committed to transforming the contemporary economy. As Pope Francis stated at our last global meeting, “Today, a new economy inspired by Francis of Assisi can and must become an economy of friendship with the earth and an economy of peace. It is a question of transforming an economy that kills into an economy of life, in all its aspects.” St. Francis referred to birds and other animals as brothers and sisters, a sentiment echoed by Pope Francis in his Encyclical Laudato Sì. As you advocate for an overlapping consensus on the virtual constitution based on CA, do you believe these sensibilities align with your project? We, the EoF youth, strongly believe they do. Before your final response, we would like to once again express our deep appreciation for your time.

MN: In general, yes. I am not a Gandhian pacifist: I think that there are just wars (for example the Second World War), and that we cannot have a world of peace without using some force against aggressors. But the goal should always be peace and friendship, and so too with animals. That is why I included a chapter on friendship between humans and other animals in the book, showing that friendship is possible not just with companion animals but also with wild animals in special circumstances. And friendship, with its emphasis on reciprocity and treating one another as ends, can serve as an ideal toward which we can strive every day. So that is the goal toward which my book points us, and I think it is very closely related to yours.