ROOTS – The Little Prince in dialogue with EoF (Part I)

by Martina Tafuro and Enrico Marcazzan

The eyes of the poor and the eyes of the children will help us to discover the wisdom of the work of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, a wisdom that can appropriately nurture “The Economy of Francesco”. We believe that this novel can shed light on the challenges that we have to face nowadays. Given the richness of insights that this book contains, we will present our contribution in three episodes. Let’s start together with the first one!

Dedication

The book is dedicated to Leone Werth, the author’s best friend. He is poor, he is hungry, he is cold, and he is completely alone. However, he has an unusual quality for an adult: he can understand a book for children! We don’t know his face, but maybe his eyes are as big as his soul. More specifically, the book is dedicated “to Leone Werth when he was a child”. A poor man, and a child inside.

The Economy of Francesco started for the eyes of the poor and from the eyes of a poor man (and a Saint, Saint Francis!). In the letter sent by the Holy Father for the event “Economy of Francesco” (Assisi, March 26th-28th 2020) to young economists and entrepreneurs worldwide, the Pope wrote that “Francis stripped himself of all worldliness in order to choose God as the compass of his life, becoming poor with the poor, a brother to all. His decision to embrace poverty also gave rise to a vision of economics that remains most timely. A vision that can give hope to our future and benefit not only the poorest of the poor, but our entire human family. A vision that is also necessary for the fate of the entire planet, our common home, ‘our sister Mother Earth’, in the words of Saint Francis in his Canticle of the Sun”.

The Little Prince can help us to embrace the eyes of the child alongside the eyes of the poor. Their eyes are complementary. This process can help us to change our views, our minds, and our thinking, exploring in a new way the reality of things, with the purpose of saving our common home, our world. As economists, entrepreneurs and change-makers, we cannot ignore this call.

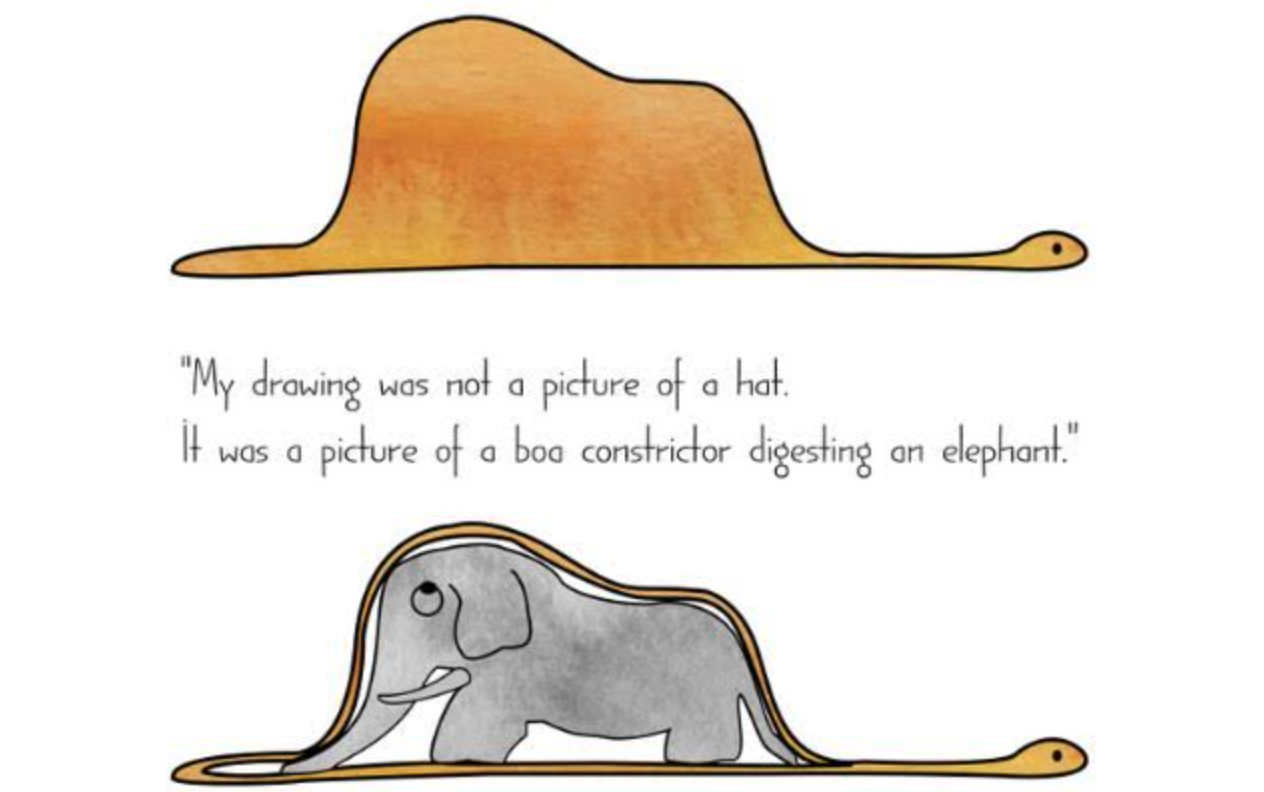

A simple hat or a snake digesting an elephant?

When he was a child, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry painted a snake digesting an elephant. But the adults thought he had painted a simple hat. The question “a simple hat or a snake digesting an elephant?” is a question that involves our eyes and the lens through which we read the world and its dynamics.

As economists, we can continue to use the lens of the adult, by answering a hat to the question, with no doubt and no care. Alternatively, we can accept the challenge of the picture of the child, by carefully investigating his painting and his question. This approach requires new eyes (i.e., a personal challenge) and new lenses (i.e., a professional challenge). We can say that this can be a matter of civil economy. The civil economy lens can help us to answer the question more properly. Maybe we were not able to answer correctly, a snake that is eating an elephant, but by continuing to see the world through the eyes of the poor and the children we can improve our answer.

In this first chapter, the topic of vocation is at the core. The adults don’t understand the painting. Thus, the child, discouraged, decides to change his dreams in face of his failure. Instead of a painter, he decides to become what people expected him to be: an airplane pilot. During his adult life, the author says that no one appropriately answered his painting question. Bridge, golf, politics and neckties were the only valid topics to discuss with them, even with the better ones.

As part of The Economy of Francesco, we have a vocation to build a common home, something that goes beyond bridges, politics and neckties. Are we prepared enough to guide a child or a poor person to discover her/his “seminal” vocation? If we had the right eyes and lenses to see the last of us, maybe we could really contribute to changing the world. Extrinsic incentives and meritocracy are the tools used by the adults to partially and insufficiently cover the issues of the missing vocation of the people. As promoters of another paradigm, we should focus on the problems of vocation starting from the children and their vision. We should focus on human flourishing starting from the children and the poor to change our (unsustainable) world.

In this first chapter, the topic of vocation is at the core. The adults don’t understand the painting. Thus, the child, discouraged, decides to change his dreams in face of his failure. Instead of a painter, he decides to become what people expected him to be: an airplane pilot. During his adult life, the author says that no one appropriately answered his painting question. Bridge, golf, politics and neckties were the only valid topics to discuss with them, even with the better ones.

As part of The Economy of Francesco, we have a vocation to build a common home, something that goes beyond bridges, politics and neckties. Are we prepared enough to guide a child or a poor person to discover her/his “seminal” vocation? If we had the right eyes and lenses to see the last of us, maybe we could really contribute to changing the world. Extrinsic incentives and meritocracy are the tools used by the adults to partially and insufficiently cover the issues of the missing vocation of the people. As promoters of another paradigm, we should focus on the problems of vocation starting from the children and their vision. We should focus on human flourishing starting from the children and the poor to change our (unsustainable) world.

A call to get acquainted

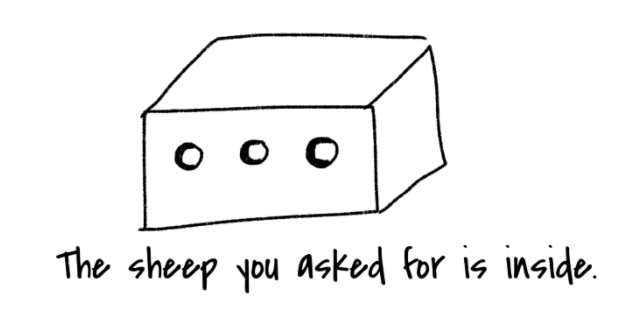

However, even if we do not find or follow our vocation since the earliest age, a call comes. A call that opens us to do something that we just know. After an accident with his airplane, in the middle of the desert an adult Antoine, dozing, is awoken at dawn by “a strange little voice: ‘Will you paint a sheep for me, please?’” The little prince asks him to draw: his initial vocation. But the author is not familiar with painting, having abandoned his dream years ago. However, intrigued and encouraged by that child to paint a sheep, the author starts again to draw. Surprisingly, the little prince recognizes the elephant inside a snake. However, he wants a sheep. And Antoine, after three attempts and failures, decides to draw a box with three holes.

“This is only his house. The sheep that you want is inside it”. “That’s what I wanted”, answered the little prince. By answering a call, which is coming from a child and is linked with his initial vocation, the author gets acquainted with a new friend.

In The Economy of Francesco, we try to answer the call of Saint Francis, a call embodied by the presence and the voice of Our Holy Father, Pope Francis, in the best way we can. Like the little prince, Saint Francis asks us to build our common home. And, as for the author of the novel, maybe there will be more than three attempts and the same number of failures to reach our goal. We should continue to think and operate in line with our values and our intrinsic motivation.

Everyone comes from the sky

The pilot and the little prince, while knowing each other, become aware that both come from the sky, but in a different manner. The pilot lives on the earth and has fallen in the desert due to an incident with his airplane, but the little prince comes from another planet. A small planet. So small, that even the sheep previously drawn could graze without surveillance. Their conversation stimulates many questions in the pilot about the origin of the little prince. Mysterious origins that are revealed only in the following pages of the novel.

In The Economy of Francesco, we should be always open to knowing the mysterious origins of the other people, while being aware that everyone comes from the sky… but in a different manner. The people that work to build our common home are characterized by many (personal and/or professional) scars, but regardless of them, are unified by a common root. The sky.

ENRICO MARCAZZAN

PhD in Management

Research Fellow at Università di Padova

MARTINA TAFURO

Sustainability

Business Communication