Underutilization of skills in the knowledge economy

by: Tatiana Vasconcelos Fleming Machado

A research on skill inequalities within the labor market of peripheral countries that seeks to give voice to countries excluded from the dynamics of capital concentration in the “knowledge economy”.

My research is concerned with the future of labour in undeveloped countries. More specifically, I investigate how technological trends impact the demand for labour in peripheral countries. The relevance of analysing labour relations in undeveloped countries is that these countries do not own the dominant technologies and do not have as advanced industries as developed countries.

Therefore, the wages of workers in peripheral countries are flattened internationally, due to the historical exploitation of knowledge suffered and the dependence (monetary, technological, etc.) on developed countries.

So, my project fully aligns with Pope Francis’ call to Re-Soul the Economy in order to combat the “love of money” and to give voice to those historically excluded from the hegemonic economy. Like Pope Francis, I am Latin American and my concern in life has always been related to the well-being of people who “walk on the same ground as I do”. Therefore, what motivates me is the sense of economic justice, that is, thinking and putting into practice ideas that empower people historically placed as secondary to the dominant economy.

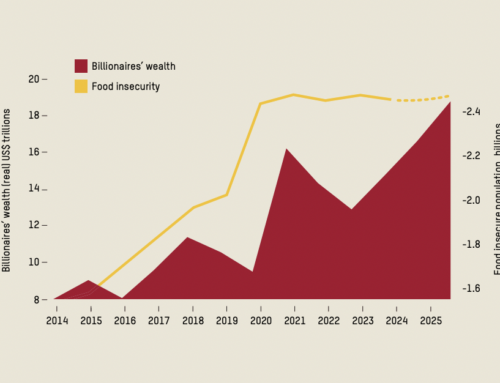

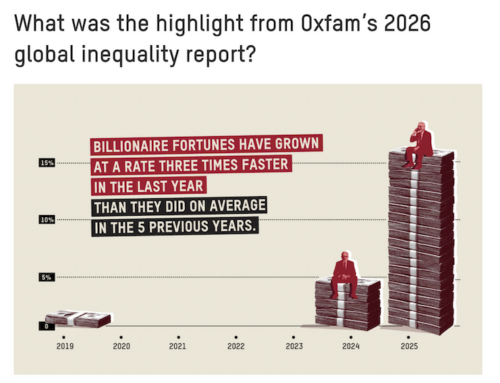

The scope of the research is on skill inequalities within the labor market of peripheral countries. It seeks to give voice to countries excluded from the dynamics of capital concentration in the “knowledge economy” (BELL, 1979). My concern is that the knowledge economy further accelerates the concentration of power in central countries, as this new model of economic system puts data and technology at the forefront.

In the globalized world, knowledge is gaining prominence over other factors of production (land, labour and capital) (GUILE, 2008). The knowledge economy brings with it the problematization of the increased concentration of capital power, evident in the formation of intellectual monopolies (RIKAP, 2021). As a result, countries that own the technologies are the ones that control capital flows. Knowledge is increasingly monopolized in the hands of a few companies, which are located in a few developed and industrialized countries.

This trend reinforces the strategies of large companies to seek low labor in developing or undeveloped countries that started in the 1990s. With the knowledge economy, data are the most precious assets and are increasingly concentrated in data centers or in the form of property rights of large companies.

In the developed industrialized world, there is a general trend of increasing the search for knowledge and qualifications (PEREZ, 2010), whose experiences of educational upgrading and qualification requirements are correlated with advances in technology.

However, in some undeveloped countries, such as Brazil, “educational upgrading indicates an increase in the incompatibility between education and occupation” (MACHADO; OLIVEIRA; CARVALHO, 2003, p.8). That is, as the degrees of schooling increase, the compatibility between knowledge accumulation and tasks performed is reduced.

This information made me reflect a lot. One of the questions I want to answer in my research is: will the new 4.0 technologies further accelerate vulnerability and the mismatch between skills and occupation in the labor market in peripheral countries? Can digitization using green technologies in companies in peripheral countries regress (or even reverse) the possible acceleration of the mismatch between skills and occupations in these countries?

One of the factors that differentiates developed from non-developed countries in the trends of educational upgrading and increase in the talent pool is the technological intensity applied by industries. Industrialized developed countries have a large physical, capital and human resource infrastructure. The capital stock is related to the increased technological intensity of firms, demanding for more qualified professionals. However, some undeveloped countries pollute much less and are much more environmentally friendly in their energy mixes. If these countries know how to digitize their “green assets”, they can increase productivity and create better quality jobs.

“One of the questions I want to answer in my research is: will the new 4.0 technologies further accelerate vulnerability and the mismatch between skills and occupation in the labor market in peripheral countries? Can digitization using green technologies in companies in peripheral countries regress (or even reverse) the possible acceleration of the mismatch between skills and occupations in these countries? “

Another factor that differentiates countries is the position in the International Division of Labor (outcome of globalization). The underutilization of skilled labour in undeveloped countries is a consequence of the heterogeneous distribution of wealth in the globalization of the economy. There is a reconcentration of the best jobs in rich countries, while the industrial peripheralization that took place after World War II is weakened. Thus, peripheral countries suffer from high unemployment rates, a decreasing share of salaried employment and an increase in precarious jobs (POCHMANN, 2004).

Undeveloped countries suffer from a double extraction of labor by large companies from developed countries: i) low-skilled manual and routine knowledge; ii) high-skilled knowledge concentrated in Universities, mainly from Brazil, India, South Africa and Argentina (RIKAP, 2021). In this way, possibilities for using local knowledge for the development of undeveloped countries are being undermined.

The demand for simple and routine knowledge from rich countries to peripheral countries subjugates peripheral national macroeconomic policies, creating a barrier to industrial development in non-developed countries (POCHMANN, 2015).

The extraction of qualified labor from non-developed countries by large companies located in developed countries is also worth mentioning. The attraction of qualified labor to integrate the pool of talent in rich countries is an obvious phenomenon, an example of which are the strategies of the United States and the United Kingdom.

The United States has a drop in the number of completions of higher education courses by nationals, as shown by McKinsey research (2023). The growth of enrollments by nationals is reducing, which is why the survey warns that universities should review the reasons for the benefits of obtaining a higher education degree, in addition to looking at issues of inequalities between social classes. What the study concludes is that the perception of costs, of debts with loans, to obtain a degree in the United States weighs more than actually acquiring knowledge. However, the labor market in the country continues to value those with a higher education degree, as the US invests massively in technology and innovation, given that 86% of new job openings projected to be created by 2030 require a high degree of scientific knowledge and technology, such as cybersecurity posts. Therefore, companies in the United States seek to attract talent from abroad to compose their pool of scientific and technological knowledge, aiming to overcome the challenges of university dropouts in the country.

According to “The Migration Observatory” of the University of Oxford (2022), the United Kingdom has also increased its talent pool with foreign labor. Even with the argument of Brexit (2020) to contain migration, what is observed is a change in the profile of migrants in the country and not a decrease in volume. The immigrants who arrived in the United Kingdom in recent years change the profile of the labor force exercised by migration in the country. Before, immigrants were mostly of European origin, with low qualifications, from poorer countries on the European continent, who went to work in the countryside or in smaller cities. Currently, there is a greater influx of immigrants with a high level of income and high qualification, coming from countries like Nigeria, India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, who stay in the big cities and oxygenate the knowledge economy.

Thus, the labor market in peripheral countries is a reflection of several factors. With the acceleration of 4.0 technologies and the position of non-developed countries, there may be a greater mismatch between skills and occupations in the labor market of these countries. However, there seems to be a window of opportunity for some peripheral countries in green

digitization to create more qualified jobs and reduce technological dependence, which my research seeks to investigate further.

REFERENCES

BELL, D. Cultural contradictions of capitalism. New York: Basic Books, 1979

GUILE, David. O que distingue a economia do conhecimento? Implicações para a educação. Cadernos de Pesquisa, v. 38, n. 135, p. 611-636, 2008.

MACHADO, Ana Flávia; OLIVEIRA, A. M. H. C.; CARVALHO, Nayara França. Tipologia de qualificação da força de trabalho: uma proposta a partir da noção de incompatibilidade entre ocupação e escolaridade. Texto para discussão, n. 218, 2003.

MCKINSEY & COMPANY. The Skills Revolution and the Future of Learning and Earning. World Government Summit, 2023.

PÉREZ, Carlota. Revoluciones tecnológicas y paradigmas tecno-económicos. Cambridge Journal of Economics, v. 34, n. 1, p. 185-202, 2010.

POCHMANN, Marcio. Reestruturação Produtiva. Rio de Janeiro: Vozes, 2004.

POCHMANN, Márcio. O emprego na globalização: a nova divisão internacional do trabalho e os caminhos que o Brasil escolheu. Boitempo Editorial, 2015.

RIKAP, Cecilia. Capitalism, power and innovation: Intellectual monopoly capitalism uncovered. Routledge, 2021.

THE MIGRATION OBSERVATORY. University of Oxford, 2022. https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/migrants-in-the-uk-labour-market-a n-overview/

Tatiana Vasconcelos Fleming Machado

PhD candidate in Economics at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ)

Research assistant of the Industry and Competitiveness Group of the Institute of Economics at the

Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (GIC-IE/UFRJ).

Researcher at Economy of Francesco, co-founding Pacar School, a project for teaching ICT

in public schools in Zambia.