Nedelsky: the revolution of care begins with time

by Luca Iacovone

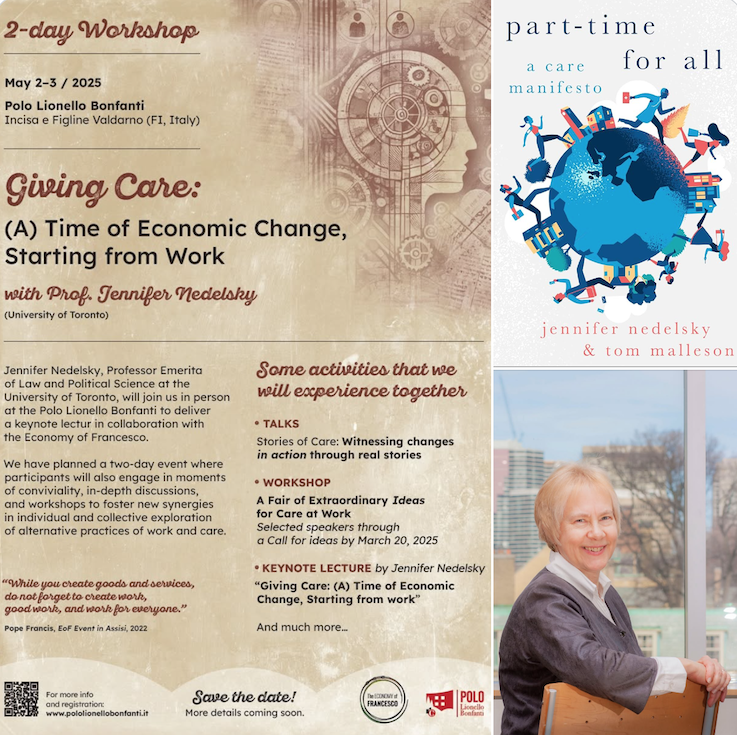

from this interview, the article published in Avvenire – “L’economia Civile”, 9 April 2025

LI: You were one of the first voices to believe in the journey of The Economy of Francesco, especially in the “Work and Care” village, which now connects young people from all over the world. What struck you about this experience? And why, more than ever, do we need a global space to rethink the relationship between work and care?

JN: There are scholars and activists all over the world concerned about the state of “work” today, and others concerned about the crisis of care. But there are few who focus on the ways they are inevitably interconnected. The “Work and Care” village allowed the connection to be made. Right now deep problems in both domains are only getting worse. We cannot have a humane life when care is denigrated and work is largely oppressive and underpaid.

LI: In your book Part-Time for All, you propose an idea that is as simple as it is revolutionary: working less, to have more time for care. Yet, outside the so-called “care market”, taking care of others is still often seen as “wasted time.” Why is it so hard for us to recognize its value when it isn’t commodified?

JN: I am glad to have the question in this form, because many people still think that the solution to the low status of care is to pay more for it, and commodify more care in the household.

But our proposal is to increase the amount of unpaid care, so that everybody has the experience of doing it, which I say more about below. We believe that when everyone understands the value of care, they will see that paid care needs to be well paid, and respected. Right now, care is devalued throughout the Western world, paid care is paid badly, and unpaid care is something women do and receive little respect for (despite romanticizing motherhood). When everything in the culture tells us care is of little value, it is very hard to believe it is not a waste of time. I still feel a struggle to believe that care of the household is as important as my scholarship.

LI: You describe care as a transformative experience—not only for those who receive it, but also for those who provide it. What changes when people in positions of political and economic power personally engage in care work? In your view, can there be adult citizenship—or a fully functioning democracy—without time devoted to others?

JN: The active practice of providing care allows people to experience the way care builds relationships and relationships need care. In the book we argue that people learn humility, and the capacity to take the perspectives of others, because they need to in order to provide good care. This is a vital capacity in a democracy. Right now most politicians are simply ignorant about the importance, the satisfactions and the demands of care. This makes them bad decision-makers for policy in almost every area, from transportation, to health care, to work place structures, to immigation.

LI: This May, you’ll be with us again at the Polo Lionello Bonfanti for the Giving Care workshop. For those who’ve been part of the Work and Care village for years, and for those just beginning to explore these themes, what do you hope might emerge from those days together?

JN: I am especially interested in combining rethinking the ownership of productive enterprise (such as creating co-ops) with building in time for care. This is one of those spheres where the world of people interested in work rarely intersect with those focused on care. We urgently need new forms of ownership so that workers have a say in their workplaces and reap the benefits of their productivity. And we need forms of ownership that take the local communities, and the more-than-human impact of their production into account. We need to expand our categories beyond capital and labour.

LI: If you could imagine a small, realistic utopia for the next ten years—something you hope might begin to take root thanks to the journey of EoF—what would it be?

JN: I would envision a community in which all the good and services were provided through cooperative enterprises where decisions were made by the people who provided capital investment, the people who provided labour, representatives of the people who lived where the enterprise was located, and people responsible for attending to the impact of their work on people and the more-than-human world elsewhere. I would picture no-one doing paid work more than 30 hours a week. Consumption would be less that currently for the upper middle class, but it would matter less. It would not be important for status, which would be very equal. People would respect one another for the kind of care they do as well as for their material production. Everyone would be part of communities of care where they take long term responsibility for each other’s care needs. And a system of equitable taxation would raise the money necessary for public provision of health-care, education, transportation and the special social services needed by people with disabilities. I picture everyone as leading far more relaxed lives, lives shaped by the joys of the connections of care—again to one another and to the earth community.