Oxfam, Inequality and the Question We Avoid:

What Is the Economy For?

by New Economic Perspectives Thematic Group – EoF Academy

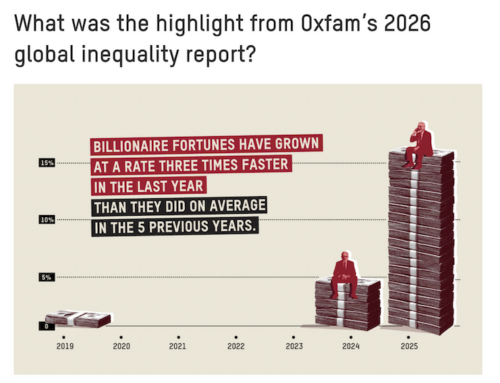

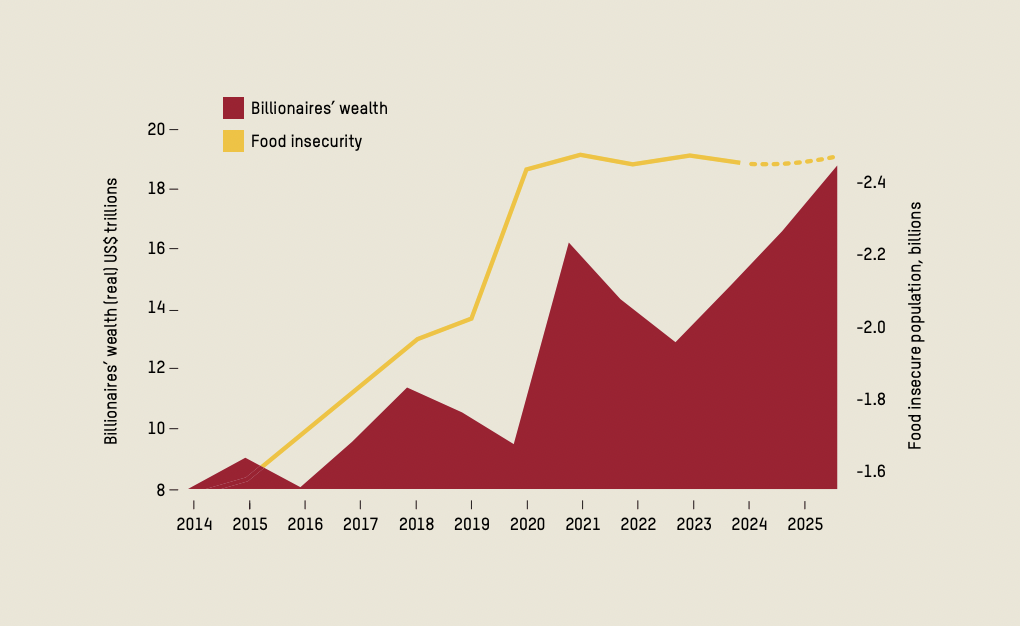

Oxfam’s latest report on global inequality offers one of the clearest and most unsettling diagnoses of our economic moment. Inequality is not only worsening but also accelerating. Wealth at the top is growing faster than income, productivity, or social well-being. Billionaire fortunes have surged while billions of people struggle to secure food, housing, and dignity. Even more worrying, economic inequality is translating directly into political inequality: the report shows how extreme wealth multiplies political influence by thousands of times, distorting democratic institutions and public policy in favor of the few.

Oxfam is right to insist that this is not a natural phenomenon. Inequality is not an accident; it is produced. It is engineered through tax systems, deregulation, monopolized markets, weakened labor protections, and captured states. The report powerfully names the problem: when economic power concentrates, political power follows. Democracy erodes, and repression replaces distribution.

Yet there is also a silence in the report, or at least a weakness, when it comes to solutions. The implicit answer often seems to be global wealth redistribution, higher taxes on the ultra-rich, and stronger international coordination. While morally appealing, this approach runs into serious political, cultural, and anthropological limits. In a world marked by geopolitical fragmentation, weakened multilateralism, and growing distrust of global governance, centralized redistribution risks remaining an abstract aspiration rather than a lived transformation.

This raises a deeper question, one that the Economy of Francesco community has long insisted on asking: what is the economy actually for?

When Economics Loses Its Purpose

If the purpose of the economy is misaligned, economics has very little to add. Technical fixes cannot heal a system that no longer knows why it exists.

Oxfam’s data shows that food insecurity is rising alongside billionaire wealth. This is not coincidental. Food inequality tracks closely with the organization of global supply chains: highly financialized, concentrated, and optimized for profit extraction rather than nourishment. Food becomes a commodity first, a human need second. Farmers are squeezed, workers are underpaid, ecosystems are depleted and consumers pay more for less.

From an Economy of Francesco perspective, this is not merely a market failure. It is a failure of purpose. An economy that produces hunger alongside excess wealth is not malfunctioning; it is functioning exactly as designed.

The question is then, not only how to redistribute outcomes, but how to redesign structures.

Power, Capture and the Missing Macro Lens

One of the most important contributions of the Oxfam report is its insistence on the political dimension of inequality. Extreme wealth does not remain passive. It buys media, shapes narratives, funds lobbying and captures regulatory institutions. When capital captures the state, public policy stops serving the common good and starts protecting accumulation.

This insight echoes a long tradition in economic thought. Wilhelm Röpke (1960) warned that when markets are no longer embedded in strong political and moral institutions, they collapse into oligarchy. Hilaire Belloc (1912) made a similar point in different terms: when ownership concentrates excessively, societies drift toward either servitude or authoritarian control.

The Civil Economy tradition helps us name what is missing here. Much of the ethical discourse in alternative economics focuses on virtues: reciprocity, care, fraternity, and the common good. These are essential. But virtues alone are not enough if institutions reward anti-virtue behavior.

As the Civil Economy literature acknowledges, virtue ethics must be complemented by institutional ethics. Moral individuals operating inside immoral systems cannot, on their own, change the system (Martino, 2020). This is where the Economy of Francesco movement must push its thinking further: often it speaks powerfully about values at the micro level, but too often leaves the macro organization of markets, competition, and power under-theorized. We need both.

Democracy and the Economy Are Not Separate

A key illusion of modern economics is the idea that economic reality can be separated from social and political reality. Oxfam’s report decisively disproved this. Economic inequality produces political inequality, which in turn reinforces economic inequality. The cycle is self-perpetuating.

From this perspective, democracy in politics is to the economy what a social market economy is to capitalism. Markets require rules, limits, and anti-monopoly enforcement not to suppress freedom, but to preserve it. Free competition only exists when power is prevented from concentrating.

Here, Oxfam’s emphasis on “resisting the rule of the rich” is crucial. The challenge is not wealth as such, but unchecked wealth, wealth that escapes accountability, territorial responsibility, and social embeddedness.

From Global Redistribution to Embedded Capital

This is where a different path becomes visible. If economic power cannot be democratically abolished without abolishing private property itself, then the realistic alternative is not global redistribution, but the structural embedding of capital within political communities. When production, ownership, and responsibility remain closer to the “household”- the oikos- capital becomes visible, accountable and socially constrained.

This does not mean nationalism or isolation. It means recognizing that real economic transformation happens where people can see consequences, organize collectively, and hold power to account.

Cooperatives, steward-ownership models, social enterprises, local food systems, and economy-for-the-common-good frameworks are not marginal experiments. They are institutional designs that reconnect wealth creation with responsibility. They are easier to govern locally than globally, and they allow subsidiarity and solidarity to become structural principles rather than moral slogans.

From a systems-change perspective often echoed within the Economy of Francesco, even partial shifts in ownership and governance structures can generate non-linear effects on inequality and social cohesion.

Jubilee, Liberation and the Bigger Levers

The biblical tradition of the jubilee reminds us that economic systems periodically require reset mechanisms. Not because people are immoral, but because systems accumulate distortions over time. Debt cancellation, land rest, and limits to accumulation were not utopian ideals; they were governance tools.

Oxfam’s report implicitly gestures toward this logic, but often remains focused on redistribution rather than de-concentration. The deeper level is not only moving wealth after it has accumulated, but preventing excessive accumulation in the first place.

This means:

- Strong anti-monopoly policies

- Limits on political lobbying and media ownership

- Protection of labor organizing

- Re-embedding food, care, and ecological systems into local economies

Civil society plays a decisive role here not as a third sector politely balancing state and market, but as a counter-weight capable of resisting fused political-economic elites. It does so by fostering fraternity, raising the voice against social disparities, and developing human links that provide a soul that humanize the economy.

From Diagnosis to Direction

Oxfam has done the world a service by naming the reality we are already living in: a choice between oligarchy and democracy. But naming the problem is only the first step.

The Economy of Francesco is called to engage the bigger levers: institutional design, power distribution, ownership models, and the moral limits of markets. Virtue without structure is fragile. Structure without virtue is oppressive. Only together can they sustain a humane economy.

The task ahead is not to dream of a perfectly equal world administered from above, but to patiently rebuild economies that serve life from within economies where food feeds people, wealth serves communities, and power remains accountable.

That, ultimately, is the economy worth resisting for, and building together.

—