Why Economic Ethics Still Matter

800 Years After Francis

by the EoF editorial team

Eight hundred years after the death of Saint Francis of Assisi, his life and thought continue to bear fruit — and to plant seeds still waiting to blossom.

Among those seeds are words that remain unsettling: poverty, fraternity, mercy, common life. Words that question not only personal conduct, but also the very foundations of economic thought and global systems of value.

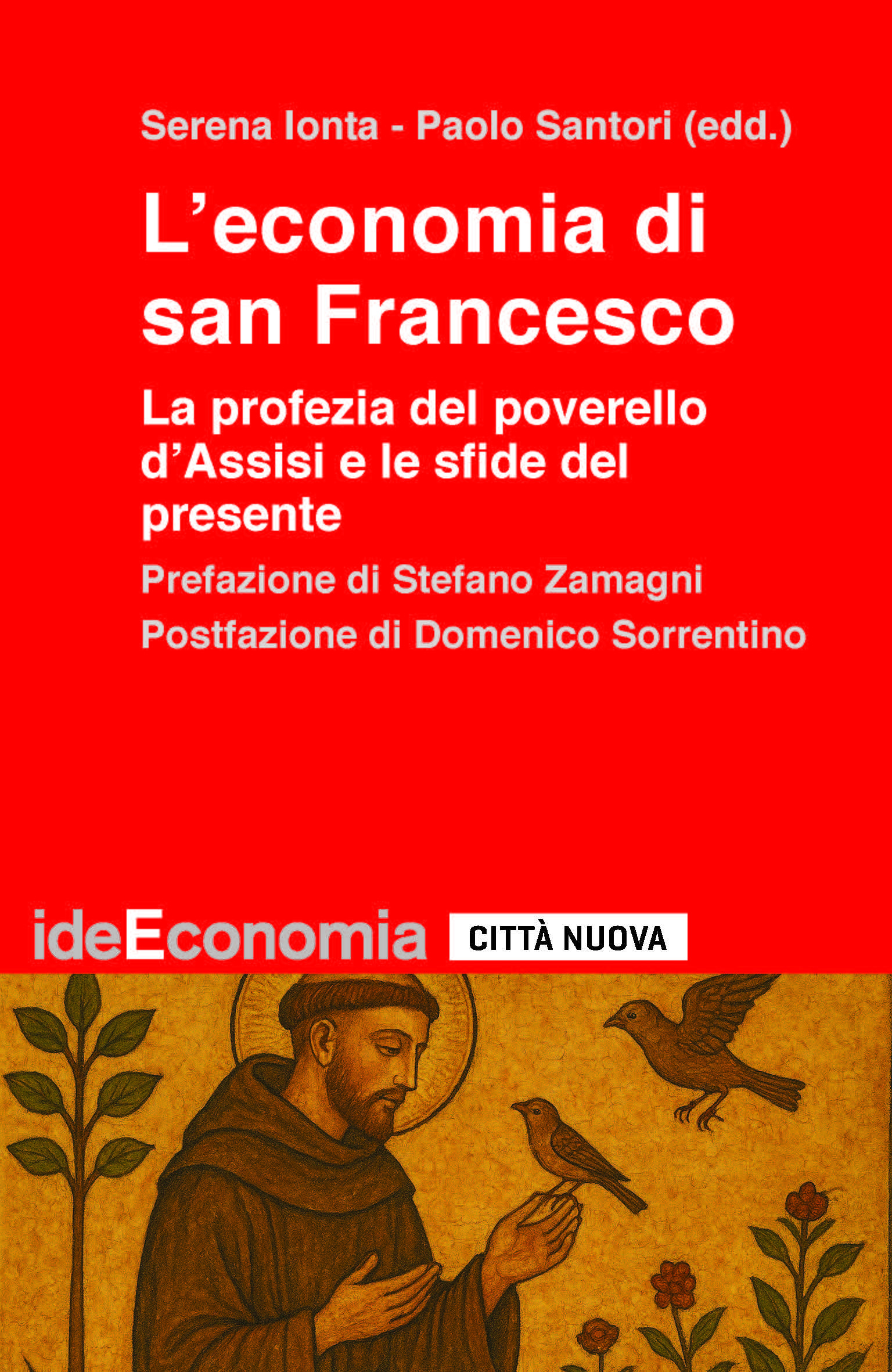

The forthcoming volume L’economia di San Francesco – La profezia del poverello d’Assisi e le sfide del presente, featuring contributions from 14 young authors from the international The Economy of Francesco community and edited by Serena Ionta and Paolo Santori, to be published by Città Nuova, revisits a demanding question: what remains today of Francis’s prophetic vision within our economic systems? What fruits have matured — and what seeds are still awaiting cultivation?

In his preface to the book, Professor Stefano Zamagni describes Francis as a prophet marked by an extraordinary sympathy for life — not a man against the world, but a man with all. While some spiritual traditions sought to love God by despising the world, Francis united love for God and love for creation, recognizing every creature as a sign of divine presence. He could not say “Brother Sun” without saying “Sister Moon.” Not an isolated individual, but a relational being.

This relational vision lies at the heart of the challenge facing contemporary economic thought.

Today, discussions about development often revolve around efficiency, growth, or optimization. Yet Franciscan prophecy invites a different measure: integral human development understood as liberation — from hunger, ignorance, exploitation — but also liberation with. As Zamagni reminds us, freedom is not only freedom “from” and freedom “to,” but also freedom “with.” One cannot be fully free alone, detached from the freedom of others.

In an age marked by aggressive individualism and widening fragmentation, this insight becomes urgent. The question is no longer whether we live in society, but what kind of society we choose to inhabit — one grounded in principles that separate the good of the individual from the good of others, or one that recognizes their deep interdependence.

Economic ethics, therefore, is not a marginal discipline. It is a civilizational question.

The paradigm of civil economy, to which many of the contributors to the volume refer, reminds us that there is no single, natural model of market economy. There are multiple models — each rooted in a particular cultural and ethical matrix. Choosing among them is not merely a technical matter of efficiency, but a moral and political act.

This becomes even more pressing in a pluralistic world that often rejects the idea of a shared ethical horizon. Contemporary societies tend to retreat into relativism, assuming that avoiding ethical questions is the safest way to prevent conflict. Yet a society cannot endure on proceduralism alone. It requires a meaningful common ground — not uniformity, but what Zamagni calls an “inter-ethic”: a shared space generated through encounter among diverse cultural traditions.

This is precisely the horizon that inspires The Economy of Francesco.

Launched by Pope Francis in 2019, the international project brought together hundreds of young scholars from across the world to rethink economic life in light of fraternity, care, and the common good. The forthcoming book, and the academic conference At the Roots of Economic Ethics, are part of this broader mission: to ask how Franciscan thought might once again enter “into service” within economic theory and practice.

Francis’ poverty, as Zamagni notes, is not simply the absence of possessions. It is the acceptance that nothing is exclusively one’s own. In a time when algorithmic management and performance ideologies risk reducing human beings to variables, the Franciscan perspective recalls another dimension of economic life: participation, co-authorship, responsibility.

Albert Einstein once warned that scientific and technological progress, if not guided by a deep concern for unresolved human problems, could turn human creations into a curse rather than a blessing. As Stefano Zamagni observes, if we replace the word “concern” with “responsibility,” we obtain a powerful description of the task before us today: ensuring that economic systems serve human flourishing rather than undermine it.

Eight centuries later, Francis’ prophetic words remain demanding — even scandalous. But perhaps precisely for this reason, they remain necessary.

To return to the roots is not an exercise in nostalgia. It is an invitation to rethink the present.

And that is why economic ethics still matters today.