Del Mastro: Victims of human trafficking are victims of the current economy

In the framework of World Day Against Human Trafficking, we interviewed Nicolás del Mastro, a young Argentinean who is dedicated to this cause from the Alameda Foundation. He tells us why the issue of trafficking matter so much in an economic environment. «A system that puts at the center the “god” of money, that alters all the processes of production to maximize profits, that maintains that a human being is an instrument, a means, is just one more commodity, merchandise, used needed to produce more money.»

Nicolas del Mastro is a youth of The Economy of Francesco (EoF) who will join the Global Event in September this year. He is from Argentina and makes part of a non-governmental organization called the Alameda Foundation, which for 20 years has been working in different parts of Argentina in the fight against the trafficking and exploitation of people.

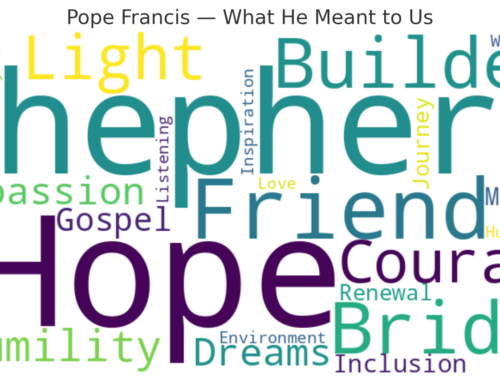

Nicolás: Nowadays we fulfill several functions in a government institution, whose creation we promoted through law, toward an economy without trafficking of human beings. This organization began amid the profound economic crisis that Argentina experienced in 2001. After that crisis, some ventures were organized on the outskirts of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, to help guarantee food security for the most vulnerable people. While there, we listened to the stories of the children of the migrant population who were being exploitated in clandestine textile workshops. That was when we began working against the mafias in the territory. On that “journey,” we met Cardinal Bergoglio, who today is Pope Francis. He, with us, gave voice to the victims’ demand for justice. That was the beginning of this work, of this 20-year-long commitment against trafficking and exploitation of people.

Can you share, perhaps, any experience of what the Foundation was like back then with Cardinal Bergoglio at the helm?

Nicolás: At that time the state did not have laws, that is, there was no criminal prosecution of these crimes, even though trafficking is an organized crime. There was a lot of community participation in granting a job opportunity in the face of the painful situations that the victims were going through. What was first done was to listen to the relatives of victims and demand justice. Often the best sign for these situations was the Holy Mass, celebrated, for a community without slavery, forced labor, or exclusion. Cardinal Bergoglio at that time presided over the Mass. Many times the Mass was celebrated in some large square of the city, among the offerings were legal files that were not acted upon in the inhuman justice system or the tents that had accommodated the relatives of the victims of a clandestine workshop that was set on fire. And at that time, it was not politicians nor any state institution, but the Church that walked side by side with those who had been hurt or injured.

This interview takes place, above all, in the context of the “World Day Against Trafficking in Persons”. So, let’s start from a common field. How do we define trafficking right now?

Nicolás: Some people describe trafficking and the exploitation of people as modern-day slavery, the slavery of the 21st century. We are talking about a crime, a transnational crime. We are talking about organized crime. This is how it is defined by the Palermo Protocol, an international instrument that countries have and that a great number of countries have ratified, committing to the fight against one of the most serious violations of human rights. It is a crime that affects human dignity.

That is why some people, such as that Pope Francis, raise their voices to condemn these crimes which include recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring, or receipt of persons, using threats or physical force, or other forms of coercion, for the purpose of exploitation, that is, to obtain a profit. The profits that the mafias generate from trafficking people, that is, from people who are vulnerable, either because they are migrants, because of their gender status, or because of their lack of access to education or health care. From that vulnerable starting point, their will is controlled, and they are transferred to other places. And that transfer implies depriving them of the life and home they’ve known, thus creating a greater dependence on the person who transferred them.

Thus, they are reduced to and used as an object, as merchandise. Human trafficking ignores the fact of the identity of the person, their nationality, their culture and their freedom. And it has different forms. Like all crimes, trafficking adapts to the economy, the territory and to cyberspace (for example). Trafficking is a way of obtaining resources, so as to make a profit from a human person who is reduced to an object.

Why does the issue of trafficking matter so much in an economic environment?

Nicolás: It is key to the economy, because in reality, when we propose the need to think, to work, and to make a new economy, an economy with a face, with a human soul, we must also take care of those who are the victims of that economy… that is, the people discarded by this disposable culture, this throw-away culture, as Francis defines it. Thus we consider the victims of trafficking. A system that puts at the center the “god” of money, that alters all the processes of production to maximize profits, maintains that a human being is an instrument, a means, is just one more commodity, needed to produce more money. So, it is necessary to remember that the main focus of our economy cannot be maximizing profits. If we want a new economy, we must inevitably think about an economy without human trafficking and therefore we need just, equitable and, sustainable communities, without human slavery or exclusion. And to reach that goal, we need to work with these processes, to think about processes that do not maximize profit at the expense of the bodies of impoverished people or people who are excluded.

Job insecurity, child exploitation and, the lack of economic autonomy for women all precipitate occasions for sexual exploitation. The situation is worsened by the use of online platforms that attract clients who are then taken advantage of and used for financial gain.

We need to change the basis, the substance of our economic structure. This is what Laudato Si’ tells us very clearly, stating. that we are experiencing a socio-environmental drama. We need to listen to the cry of the poor who raise the need for an economy that does not exploit them, that no longer uses them for finincial gain.

Could we talk about industries that feed on trafficking? What are they like, how do they work, and how can we identify them?

Yes, there is undoubtedly a market linked to human trafficking, a market that offers the right environment for all these mechanisms to proliferate. Not to mention everything that has to do with financial gain. Trafficking is one of the three most profitable crimes in the world. After organ trafficking, tissue trafficking, arms trafficking and, drug trafficking, there is human trafficking. And it has increased with the shift of our everyday life to online platforms. And what we also find is that in many value chains linked to the ‘reprimarisation’ of the economy, which Francis defines in Laudato si’, as the reality that the global south provides the raw material, that extractive mechanism, that mechanics of primary production.

So, the answer to your question is: there are many. Not to mention the large value chains of those linked to mining, linked to the need of many workers outside their homes for long periods, which are prone to the sexual exploitation of women and the exploitation that occurs through forced labor, slave labor and reduction to servitude.

Trafficking is a global phenomenon, as we can now see. Conditions that promote it increase with conflicts and the global phenomenon of war that we are experiencing, the “third world war” fought “piecemeal,” as defined by Francis. It is a value chain that applies its technocratic paradigm and, uses any mechanism to maximize profit and lower costs, producing a greater accumulation of wealth and efficiency. People are victims of all these industries linked to reprimarisation, and obviously also to those of automation in the field of manufacturing. This new world of work must value people and stop discarding them.

Since we’ve talked about how to identify it, now we also ask ourselves: how can we end this scourge that moves millions of black-market dollars around the world?

We first need to understand that this scourge, an expression of organized crime, should not find governments disorganized or a disorganized community. Thinking about dismantling the economic structure, the first step is institutional political commitment. But at the same time, what is needed is the implementation of programs that allow the reconstruction of a new horizon, a prospect of life for people who survive the crime of trafficking. And that means providing land, housing, and work. This is what Francis proposes as the plan that can answer the claim of the popular movements, of the social movements, as an agenda that allows economic autonomy for the discarded sectors of society in which people are victims of this economy. And obviously, it also has to do with a community that is committed and that says “enough is enough,” that says “no” to the mafias.

We are less than two months away from the event of Assisi. Taking into consideration the context we face, would you like to give us a final message about trafficking, or a message for the young people who are preparing for this meeting in Assisi, in which above all, we will take on a commitment to build a new economy?

I would like to remind those young people who responded to this proposal, to this call of Pope Francis to work for an economy with a human face and soul, adapted to this moment in which we are living and in which we want to be protagonists, I would like to remind them that the future enters the world through us, as Francis says, and not through any mailbox. What we want is to work for just, equitable, inclusive communities that guarantee land, shelter, and jobs so there will no longer be people who are enslaved or excluded. And that requires commitment.

We need to put back at the center of life the relationship with our brothers and sisters, with the earth, with the common home, not trying to maximize profits or putting the god of money at the center. This is what our commitment needs to be. And that’s what we’re going to do, that’s why we are going to Assisi, to reflect, study and work to develop an economy with a human face and soul.